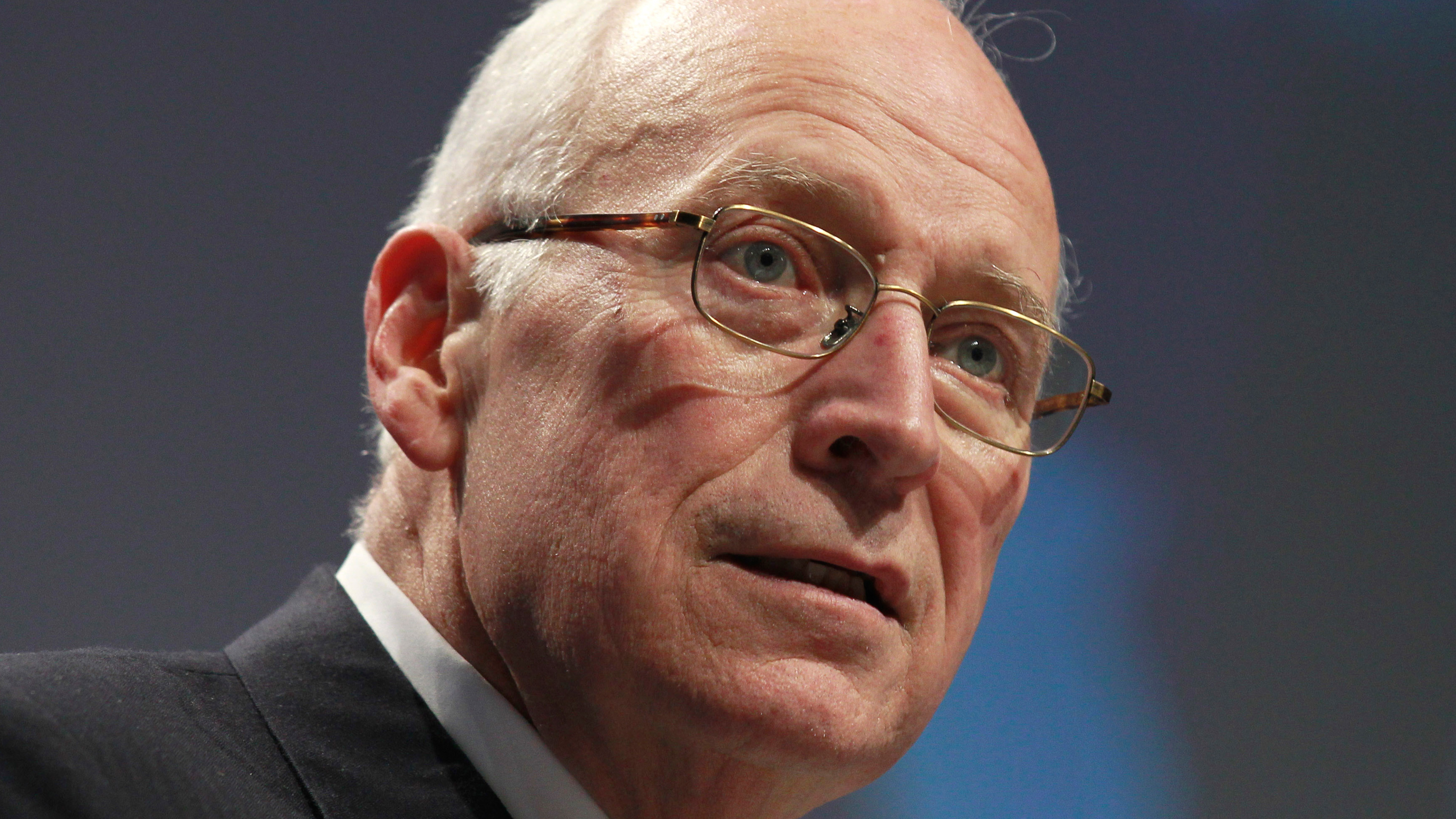

Former Vice President Dick Cheney, considered by many political observers to be the most politically active and influential vice president in U.S. history, died on Monday night, his family said. He was 84.

Cheney’s wife of 61 years, Lynne, his daughters, Liz and Mary, and other family members were with him on Monday night, the family said in a statement, adding that the former vice president died of complications of pneumonia and cardiac and vascular disease.

“Dick Cheney was a great and good man who taught his children and grandchildren to love our country, and to live lives of courage, honor, love, kindness, and fly fishing,” the statement said. “We are grateful beyond measure for all Dick Cheney did for our country. And we are blessed beyond measure to have loved and been loved by this noble giant of a man.”

Cheney worked for nearly four decades in Washington. He served as the youngest White House chief of staff under President Gerald Ford; represented Wyoming in the U.S. House of Representatives — where he worked with congressional leadership and President Ronald Reagan; was secretary of defense under President George H.W. Bush; and later served two terms as vice president under Bush’s son, President George W. Bush.

He was also CEO of Halliburton, an energy company based in Texas that had a global presence.

When terrorists attacked the United States on Sept. 11, 2001, it was Cheney who first took charge while the president was out of Washington.

“When the president came on the line, I told him that the Pentagon had been hit and urged him to stay away from Washington,” Cheney recalled in his memoir, “In My Time.” “The city was under attack, and the White House was a target. I understood that he didn’t want to appear to be on the run, but he shouldn’t be here until we knew more about what was going on.”

He and senior staff gathered at the Presidential Emergency Operations Center, where they monitored the horror unfolding.

“I stayed up into the morning hours thinking about what the attack meant and how we should respond,” Cheney wrote in his memoir. “We were in a new era and needed an entirely new strategy to keep America secure. The first war of the twenty-first century wouldn’t simply be a conflict of nation against nation, army against army. It would be first and foremost a war against terrorists who operated in the shadows, feared no deterrent, and would use any weapon they could get their hands on to destroy us.”

As vice president, Cheney was also known as the mastermind behind much of the Bush administration’s strategy in Iraq.

“His power is unparalleled in the history of the republic, frankly, for that position,” John Hulsman, a research fellow at The Heritage Foundation, a conservative Washington-based think tank, told ABC’s “Nightline” in 2005.

Cheney said he looked upon his role as vice president as being an adviser to the president.

“I don’t run anything, I’m not in charge of a department or a particular policy area and for me to be out all of the time commenting on the issues of the day — pontificating if you will — on what’s going on, to some extent infringes upon everybody else in the administration, especially with those specific people who have got specific responsibilities,” he told ABC News Chief Global Affairs Martha Raddatz in an interview in March 2008, when she was a White House correspondent.

“My value to him is the fact that we can talk privately I can tell him what I think, sometimes he agrees, sometimes he disagrees he doesn’t take my advice all the time by any means,” he continued. “But the contribution that I make and my value to him, I think, is greater because he knows and everybody else knows I’m not going to be in the front pages of the paper tomorrow talking about what I advised the president on what particular issue.”

Cheney was also a leading defender of the Bush administration’s “War on Terror” and unabashedly defended the controversial enhanced interrogation techniques approved by the Bush administration against high-value detainees. He and his daughter Rep. Liz Cheney, who served as a Republican congresswoman from Wyoming until 2023, argued that those techniques, which included waterboarding — an interrogation tactic that simulates drowning — yielded valuable information from detainees. Waterboarding was used on three prime terror suspects held in Guantanamo Bay, CIA Director Michael Hayden said in 2008.

“I was and remain a strong proponent of our enhanced interrogation program,” Cheney said in May 2009, as he delivered a dueling speech to Obama’s remarks explaining why the president was ending the use of enhanced interrogation techniques. “The interrogations were used on hardened terrorists after other efforts failed. They were legal, essential, justified, successful and the right thing to do.”

And later, in the 2013 documentary “The World According to Dick Cheney,” the former vice president said, “Tell me what terrorist attacks you would have let go forward because you didn’t want to be a mean and nasty fellow. Are you going to trade the lives of a number of people because you want to preserve your honor, or are you going to do your job, do what’s required, first and foremost your responsibility is to safeguard the United States of America and the lives of its citizens.”

After his time in office ended, he remained politically active while former President George W. Bush had moved back to Texas and refrained from commenting on politics in an effort to avoid “undermining” the current president.

During President Barack Obama’s administration, Cheney emerged as an outspoken critic of the president’s national security policies — charging that Obama’s counterterrorism policies were making the country less safe.

“It has always been easy for those who are evil to kill, but now it is possible for a few to do so on an unimaginable scale,” Cheney wrote in his 2011 memoir.

“The key, I think, is to choose serious and vigilant leaders, to listen to the men and women who want us to entrust them with high office and judge whether they are saying what they think we want to hear or whether they have the larger cause of the country in mind,” he continued. “It’s not always easy to move beyond pleasing promises, but in the case of America, the greater good is so grand.”

Early life

Richard Bruce Cheney was born on Jan. 30, 1941, in Lincoln, Nebraska, to Richard Herbert Cheney, a U.S. soil-conservation agent, and Marjorie Lauraine Dickey Cheney.

When Cheney was 13, his father’s job took the family to Casper, Wyoming. There, Cheney played football and baseball, fished and hunted rabbits, according to his former U.S. Senate profile. In high school, he was the senior class president and co-captain of the football team. He also met and dated his future wife, Lynne Vincent, who happened to be the school’s homecoming queen.

What stood out most in Lynne Cheney’s mind was that Cheney “spent as much time listening as he did talking, which is pretty unusual in a teenager,” she’s quoted as saying in the Senate profile.

From Wyoming, he went to Yale University in 1959, having been recruited with a full scholarship. Poor grades cost him that scholarship and he returned to Wyoming after three semesters. He worked as a lineman for a power company, but was “headed down a bad road” after being twice arrested for driving while intoxicated, according to the Senate profile. His future wife, in the meantime, had graduated from college, gotten her master’s degree and made clear to Cheney that she expected him to return to college before they married.

He went to the two-year Casper College and later graduated from the University of Wyoming, earning his bachelor’s degree in 1965 and his master’s degree in 1966 — each in political science.

During the Vietnam War, when Cheney was draft-eligible, he received deferments as a student, and then as a registrant with a child, prompting criticism when he later ran for public office.

“I had other priorities in the ’60s than military service,” Cheney told a reporter in 1989, according to The Washington Post.

In a later Senate confirmation hearing for his nomination to be secretary of defense, Cheney said he “would have been obviously happy to serve had I been called.”

While still a college student in Wyoming, Cheney served an internship at the state legislature. It was one of two that were funded by the state’s political parties. While the other intern was active in the Young Democrats and asked to work for the lower house with its Democratic majority, Cheney’s political identity remained unformed and he worked in the Republican-led state Senate.

“You had to know every legislator,” Cheney recalled in his Senate profile, “be there when they needed you, and remember how they wanted their coffee.”

A wealth of political experience

The Cheneys each went on to pursue doctorates at the University of Wisconsin. Lynne Cheney earned a Ph.D. in British literature, but her husband didn’t finish his degree in political science. He moved on to politics, interning for the Republican governor of Wisconsin and then taking an American Political Science Association fellowship to work for a year on Capitol Hill in 1968. During that fellowship, he heard Rep. Donald Rumsfeld speak and applied to work in his office, but was rejected.

“He pretty much threw me out of his office,” Cheney recalled in his Senate profile. “Don’s impression of me was that I was a detached, theoretical, impractical academic type.”

Cheney went on to work for Rep. William Steiger, R-Wis.

His congressional fellowship required him to split his year between the House and Senate and Cheney had made arrangements to join the staff of Sen. Ted Kennedy, D-Mass., but Richard Nixon’s inauguration in 1969 “set in motion a chain of events that would propel Cheney from a congressional fellow to White House chief of staff in seven fast years,” according to his Senate profile page.

Cheney’s move from Capitol Hill to the White House began when Rumsfeld was appointed to head the Office of Economic Opportunity. Cheney sent the former congressman an unsolicited memo suggesting ways to handle his confirmation hearings and it prompted Rumsfeld to hire him. Rumsfeld also held the title of special assistant to the president and took Cheney to the West Wing for daily staff meetings. Cheney did not follow Rumsfeld to Europe when he became ambassador to NATO in 1973, instead keeping his family in Washington and working for an investment consulting firm.

When Nixon resigned in 1974 in the wake of the Watergate scandal, Gerald Ford — the vice president and former House Republican leader — made Rumsfeld his chief of staff. Cheney returned to the White House and served as Rumsfeld’s deputy. Then, as Ford braced for an uphill battle for election to the office he assumed after Nixon’s resignation, he made significant changes to his administration. He replaced Henry Kissinger with his deputy as national security adviser, named Rumsfeld his secretary of defense and elevated Cheney to be the president’s chief of staff. At 34, he was the youngest to hold that position.

After Ford lost the election to Jimmy Carter, Cheney returned to Wyoming. He initially considered running for a U.S. Senate seat, but was advised that Alan Simpson was planning to run and that he would easily win. Cheney turned his attention to the state’s sole House seat, left open by an incumbent who had announced his retirement. Cheney rented a Winnebago and campaigned with his parents, wife, daughters Elizabeth and Mary and their family dog. It was during this campaign that he suffered his first heart attack. While sidelined for several weeks, his family continued to campaign and he rose in the polls.

He won the Republican nomination for the seat and in the general election defeated the Democrat with 58.6% of the vote. Cheney was reelected to the seat five times.

Back on Capitol Hill, he rose in the ranks. In his second term, he was elected chair of the House Republican Policy Committee. He was serving on the House Intelligence Committee when news broke about the Iran-Contra scandal and his staff drafted the minority report, which accused Congress of tying President Reagan’s hands and asserted that national security would occasionally require chief executives to “exceed the laws,” according to his Senate profile page. Cheney was elected conference chairman in 1987 by the House Republicans and in 1987 he was elected as minority whip.

He appeared on track to one day hold the House speaker position — even writing a history of the position with his wife — but when President George H.W. Bush’s nomination of Sen. John Tower for secretary of defense was defeated in the Senate, Cheney was recommended as a replacement.

Defense secretary

Cheney entered the Pentagon at the end of the Cold War. During the first Bush administration, the Berlin Wall came down and the Soviet bloc came apart.

Days after Iraqi forces invaded Kuwait on Aug. 2, 1990, the president told reporters, “This will not stand, this aggression against Kuwait.”

In a hastily arranged visit with Saudi Arabia’s king, Cheney and Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf Jr. explained their proposed buildup of U.S. forces, but Cheney assured the king that defending Saudi Arabia from possible Iraqi attack defined the limits of the Americans’ aims, Cheney said, according to “America’s War for the greater Middle East” by Andrew J. Bacevich.

The king’s decision to accept the proposal did not sit well with some, including Osama bin Laden, a young Saudi veteran who had recently returned from a war in Afghanistan. He strenuously objected to relying on infidels, or non-Muslims, to solve a dispute among Arabs, Bacevich wrote. To liberate Kuwait, he offered to raise an army of guerrilla-type fighters, but his offer was rejected and he fled into exile, Bacevich wrote.

The operation began as an air campaign that pounded the Iraqi forces. Cheney then announced the beginning of the ground war on Feb. 23, 1991. There was a total blackout of news coverage that was lifted after Schwarzkopf declared the allies had achieved a dramatic success with few casualties. With the Iraqis in retreat and the U.S. having achieved its military objectives, Gen. Colin Powell, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Schwarzkopf recommended an end to the ground war. Cheney defended the decision as wise policy that avoided getting U.S. troops bogged down in a quagmire, according to his former Senate profile page.

The victory in the Persian Gulf sent Bush’s approval rating soaring, but when the economy fell into recession and a three-way presidential race in 1992, Bush was defeated in his bid for reelection by Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton.

Cheney returned to Wyoming, but was back in Washington in 1993 when he and his wife became senior fellows at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative research center. He considered running for president and even formed a campaign committee to raise funds, but abandoned the notion after Republicans took control of Congress in 1994.

In 1995, he became chairman and chief executive officer at the Halliburton Company, a supplier of technology and services to the oil and gas industries, according to the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Halliburton did business around the world, but especially in the Middle East where “Cheney’s military and diplomatic contacts could assist the company’s bids for government contracts — some $1.5 billion during his tenure,” according to his Senate profile.

Back to Washington

Living in Texas, Cheney turned down an offer to chair George W. Bush’s 2000 campaign for president, but agreed to head the selection process for his running mate.

“As I expected, Dick did a meticulous, thorough job,” Bush wrote in his memoir, “Decision Points.”

But after leading the search committee and narrowing the list to nine candidates, Bush wrote, “in my mind, there was always a tenth.”

He ultimately convinced Cheney to run with him.

“Ten years later, I have never regretted my decision to run with Dick Cheney,” Bush wrote in his memoir.

The election was held on Nov. 7, 2000, and though Vice President Al Gore had won the popular election, the electoral vote hinged on ballots in Florida. The results were not finalized until a 5-4 Supreme Court decision in Bush v. Gore — which ended the recount in Florida and awarded Bush the state’s 25 electoral votes.

Before Inauguration Day, Cheney headed up Bush’s transition effort — something none of his predecessors had done — and played a key role in helping to select the president’s Cabinet members.

As vice president, Cheney worked behind the scenes, playing a key role in devising many of the Bush administration’s controversial policies. He also emerged as the administration’s key negotiator on Capitol Hill, setting up official offices in both the House and Senate. Early on, the 50-50 split between Republicans and Democrats in the Senate made Cheney’s constitutional authority to cast tie-breaking votes in that body crucial — though Republicans soon thereafter gained majorities in both houses of Congress.

In his memoir, Bush wrote, “The real benefits of selecting Dick became clear fourteen months later.”

On Sept. 11, 2001, Bush was visiting an elementary school in Florida and Cheney was working in the West Wing when terrorists hijacked four planes. Two were flown into the World Trade Center in New York, one struck the Pentagon outside Washington and a fourth went down in rural Pennsylvania after passengers overran the hijackers.

Cheney reportedly watched television as the second plane hit the World Trade Center and after reports of a plane headed toward Washington that wasn’t communicating with controllers at Reagan National Airport, Secret Service agents rushed the vice president to the emergency operations center. By the time they arrived, there were television reports showing smoke rising from the Pentagon.

The vice president advised Bush not to return to Washington and arranged for congressional leaders to be taken to a protected location in West Virginia.

“The calm and quiet man I recruited that summer day in Crawford stood sturdy as an oak,” Bush recalled.

‘War on terror’

Following the attacks, the Bush presidency was transformed. National security became a top priority. Congress rushed the Patriot Act, giving the government greater intelligence-gathering authority, in a week. And once it was determined that the attacks had been carried out by al-Qaeda, under the leadership of bin Laden, the military was sent to Afghanistan where the Taliban had allowed al-Qaeda to operate. Hundreds of suspected terrorists were captured and prisons were erected at a U.S. Navy base at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba.

Iraq became a target in Bush’s so-called war on terror, with some members of the administration, including Cheney — who told PBS he was a “strong advocate of going into Iraq” — linking Iraq to al-Qaeda and claiming that Saddam Hussein was developing weapons of mass destruction. Neither were found to be the case.

The U.S. invaded Iraq in March 2003, marking the start of a nearly decade-long military mission and a violent insurgency.

After the GOP narrowly secured a victory in the contentious 2004 presidential election, much of Bush-Cheney’s second term was consumed with the war in Iraq and the U.S. “war on terror,” of which Cheney was considered a chief architect.

The war in Iraq led to the capture and subsequent hanging of Hussein, though the last U.S. troops would leave after nearly nine years and significant cost. Nearly 4,500 U.S. service members and over 100,000 Iraqis were killed during the war, on which the U.S. Treasury spent more than $800 billion.

As the U.S. also continued to battle a Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan, Cheney was the target of an apparent assassination attempt in 2007, when a suicide bomber struck a U.S. air base near Kabul he was visiting. The Taliban claimed Cheney was the intended target of the attack, which killed 23 people.

Public support for the Iraqi invasion gradually waned, and by the time he left office, Cheney’s approval rating made him one of the most unpopular vice presidents in recent U.S. history.

Cheney would often find himself on the defensive regarding the war.

“I believe very deeply in the proposition that what we did in Iraq was the right thing to do,” Cheney told ABC News’ Jonathan Karl in an interview on “This Week” in 2010. “It was hard to do. It took a long time. There were significant costs involved. But we got rid of one of the worst dictators of the 20th century.”

Controversies

Cheney took heat for his connections to the energy industry, facing criticism when Halliburton subsidiaries were awarded controversial no-bid contracts in Iraq. Halliburton was also the focus of a Securities and Exchange Commission investigation into accounting practices begun when Cheney was head of the company.

Other Cheney links to the energy sector also put the Bush administration under public scrutiny. Following the collapse of Enron, there were calls for Cheney to testify about his contacts with the energy giant, but he refused.

His aides were also thought to have leaked the identity of special CIA agent Valerie Plame after her husband wrote a scathing op-ed blasting the administration. Cheney was never connected, but his former chief of staff, Scooter Libby, who testified that Cheney and his superiors gave him the green light to reveal the classified documents, was later convicted.

During the 2004 presidential campaign, his daughter Mary’s sexual orientation was thrust to the forefront in the national debate over gay marriage, including a public family feud between Mary and Liz, although the Cheneys’ rarely discussed the personal family issue. Cheney was at odds with Bush’s call for a constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage, instead voicing support for a state approach.

“With the respect to the question of relationships, my general view is freedom means freedom for everyone,” he said at a campaign rally in 2004. “People ought to be free to enter into any kind of relationship they want to.”

Cheney was involved in an infamous hunting accident in 2006, when he accidentally shot Harry Whittington in the face with a shotgun while on a quail hunt in Texas. In an interview with the Washington Post four years after the incident, Whittington, an attorney, bore no ill will, calling Cheney “a very capable and honorable man.”

Heart health

In 2013, he wrote “Heart” with his longtime cardiologist, Dr. Jonathan Reiner, to chronicle his long battle with heart disease and provide insight to the medical and technological breakthroughs that have changed cardiac care around the world.

“If this is dying, I remember thinking, it’s not all that bad,” he wrote in the prologue. “It had been thirty-two years since my first heart attack. I’d had four additional heart attacks since then and faced numerous other health challenges. Now, in the summer of 2010, seventeen months after I left the White House, I was in end-stage heart failure.”

“I believed I was approaching the end of my days, but that didn’t frighten me. I was pain free and at peace, and I had led a remarkable life,” he continued.

But as his condition deteriorated, Reiner raised the possibility of having a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implanted, which could extend his life long enough to be eligible for a new heart.

The device was implanted July 2010, and in March 2012, after being on the cardiac transplant list for more than 20 months, Cheney underwent heart transplant surgery in Falls Church, Virginia.

Cheney’s long history of health problems and heart disease included five heart attacks. His first occurred in 1978, when he was 37 years old.

After suffering two more attacks in 1984 and 1988, Cheney had quadruple bypass surgery to relieve arterial blockages and multiple angioplasties. He wore a special pacemaker designed to take corrective action if his heart faltered.

Cheney suffered from a fourth heart attack in November 2000 after he and Bush were first elected.

In 2001, Cheney had a pacemaker installed into his chest designed to activate automatically if needed to regulate his heartbeat.

His fifth heart attack was in 2010, before the LVAD was implanted.

Legacy

In the years after he left office, Cheney’s spot in American history was scrutinized.

He was one of the most influential, if also most unpopular, vice presidents in history — referred to by friends and foes alike as “Darth Vader,” the “Star Wars” villain.

He worked to expand the executive powers. In a 2015 biography, former President George H.W. Bush said Cheney had too much “hard-line” influence in the use of force in his son’s White House, according to the New York Times.

Cheney’s involvement in the CIA’s controversial post-9/11 interrogation techniques followed him long after his vice presidency. Several public officials and human rights groups claimed that he should have been charged with war crimes for the so-called enhanced interrogation techniques.

He remained a champion of the program, including the use of waterboarding, even after the technique was banned under the Obama presidency. Cheney referred to a blistering 2014 Senate report that was critical of the techniques as “full of crap.”

Cheney’s eldest daughter, Liz Cheney, continued the family’s prominence in the Republican party as the House GOP conference chair, though was ousted from the post after challenging former President Donald Trump’s false claims that he won the 2020 election.

Cheney, who himself had been relatively quiet during the Trump presidency, also took on the false claims of vote-stealing, reportedly pulling together nine other former Pentagon chiefs in an opinion piece published in the Washington Post calling for a smooth transition of power.

Cheney was portrayed in the 2018 Oscar-nominated biopic “Vice,” which Rolling Stone called a “polarizing,” “flamethrowing take” on Cheney’s rise.

“I really felt like we all know that he was a powerful vice president,” director Adam McKay said during an appearance on “Popcorn with Peter Travers.” “But the more I read about it, I was just astounded by how much this guy changed history. … And then I was amazed [at] how he did it.”

Cheney did not publicly respond to the film. Throughout his career, he would brush aside concerns about his own legacy.

“I don’t lay awake at night thinking, gee, what are they going to say about me now?” he said in “The World According to Dick Cheney,” a Showtime documentary. “I didn’t worry about it a lot when I was doing it, and I thought the best way to get on with my life and my career was to do what I thought was right.”

ABC News’ Karen Travers, Jonathan Karl, Lauren King, Meredith Deliso and Benjamin Siegel contributed to this report.

Copyright © 2025 ABC News Internet Ventures.

Niko Travis is a dedicated health writer with a passion for providing clear, reliable, and research-backed information about medications and mental health. As the author behind TrazodoneSUC, Niko simplifies complex medical topics to help readers understand the benefits, uses, and potential risks of Trazodone. With a commitment to accuracy and well-being, Niko ensures that every article empowers readers to make informed decisions about their health.